EU missing out on the benefits of early HIV and hepatitis diagnosis

A new ECDC monitoring report shows that many EU/EEA countries are still not achieving the full benefits of early diagnosis for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C

In the latest monitoring report on HIV, hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) the ECDC reported that 27 countries have national HIV-testing policies, while 22 have recommendations on hepatitis B and C, only 17 have the ECDC’s preferred option of integrated testing for all three and sexually transmitted diseases. The survey covers the EU and the wider EEA area (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).

ECDC guidance on testing, which was updated in 2018, urged countries to take a more concerted effort to scale up integrated testing for HIV, hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) to reduce the number of those that are currently infected but undiagnosed. The findings reveal that while the EU/EEA has the tools to diagnose infections earlier and more equitably, these tools are not yet being fully used.

Early testing is a lifesaver

Early testing and diagnosis can lead to life-saving treatment and prevention services suppressing the virus, or even offering a potential cure in the case of hepatitis C. It can also help prevent the further spread of disease by providing awareness and an opportunity to advise on ways to reduce exposure, including through the provision of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), or in the case of hepatitis B, through vaccination.

The report estimates that there are 820,000 people currently living with HIV, 3.2 million with chronic HBV, and 1.8 million with HCV. People testing positive for these diseases in 2023 were: nearly 25,000 for HIV, 38,000 for HBV and 28,500 for HCV.

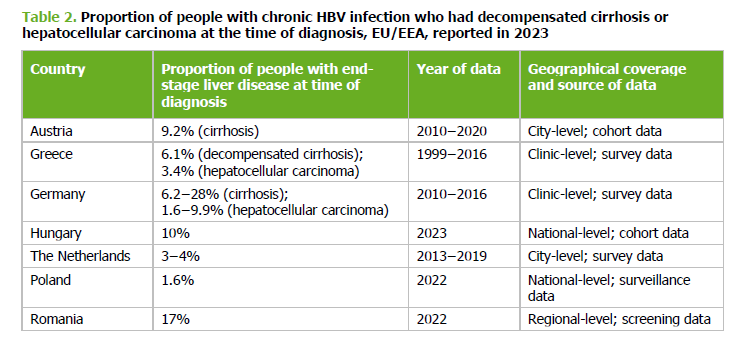

“Over 50% of HIV cases are diagnosed late,” and late-stage HBV/HCV diagnoses are common, often when liver disease is already advanced. While countries are close to meeting HIV diagnosis targets, the report finds that none of the countries with available data have reached the WHO goal of diagnosing 60% of people with chronic hepatitis B.

Late-stage diagnosis for HIV, defined as having a CD4 cell count below 350 cells per mm blood, means that the immune system is already compromised. Women, older adults (50 and over), and men or women infected through heterosexual sex were the highest proportions of this group.

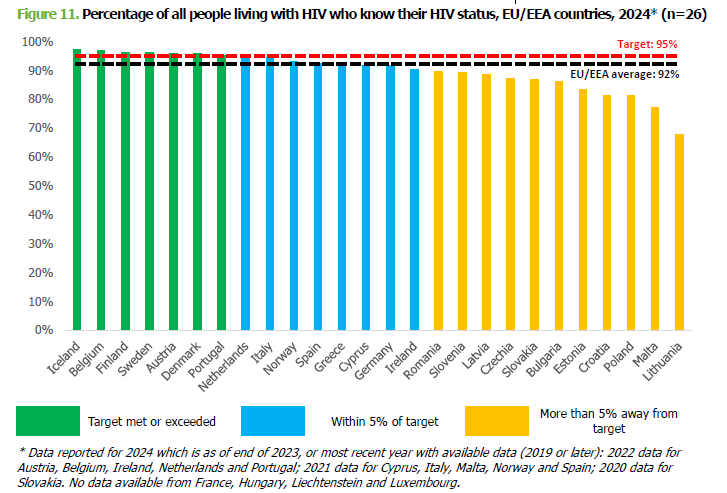

The good news is that seven countries are on track to reach the 95% testing target for the estimated number of those living with HIV, eight are nearly there, and a number of countries are more than 5% points away from the target, notably those in the centre and east of Europe.

For HBV, information on late diagnosis was more limited with only seven countries with available data. This was a similar situation for HCV, but the data were also quite dated. While countries approach HIV targets, the report finds that none of the countries with available data have reached the WHO goal of diagnosing 60% of people with chronic hepatitis B, and only three have met the 60% target for HCV. However, the surveillance of HBV and HCV are generally weaker.

The ECDC wants to see more up-to-date policies that have better inclusion of key populations based on better data, expanded self-testing, and community outreach. In particular, it calls for removing legal barriers to lay-provider testing and ensuring free access to HIV, HBV, and HCV tests for vulnerable groups.

Early testing saves lives and prevents the transmission of disease, ECDC point to the need for countries to step up to ensure that everyone, regardless of background or circumstances, can readily access timely and free testing.